In the first episode of this podcast, I described my approach to zen practice and teachings as Zen Naturalism. So it’s only expected that the question as to whether Zen Naturalism is a religion or not might arise. And of course, the response to that question depends mightily upon how one defines “religion.” And this is not a new question, especially as it relates to Buddhism. For one thing, the concept of “religion” is not an indigenous one to ancient India where what was practiced and believed was simply thought of as the natural order of life. And what the Buddha taught was referred to as both buddha-sasana, (Buddha’s teaching) or buddha-dharma, (Buddha’s dharma). With colonization of Asian Buddhist cultures, the concept of religion entered into and influenced Asian practitioner’s understanding of what and how they lived as “religion”.

Thus, when Richard Gombrich interviewed a Thai Buddhist monk for his excellent book, Theravada Buddhism: A Social History from Ancient Benares to Modern Colombo, he reports that monk saying, “Gods are nothing to do with religion.” Now, while traditional Buddhists throughout history have believed in gods as powerful beings, often seen as capable of granting worldly boons, they were not seen as omnipotent, nor omniscient, nor eternal and none were thought to be the creator of the cosmos. They are seen as trapped in the cycle of existence known as samsara, subject to birth, decay, and death. For that Thai monk, “religion” has to do with soteriology, liberation or salvation. Religion is about the matter of cultivating a proper understanding and practice of the dharma with the purpose of attaining liberation from the cycle of samsara and gods have no impact on that project. Religious practice is about the development of insight into the empty nature of all phenomena and the eradication of greed, enmity, and delusion. As Gombrich makes clear, “For Buddhists, religion is what is relevant to this quest for salvation, and nothing else.” This soteriological approach to religion and religious practice is akin to yoga, which sees itself also as a soteriological path to liberation. Interestingly, there is even a similar meaning to the words religion and yoga. Where yoga has the meaning of yoking, and by extension, joining or uniting, religion comes from the Latin religio which means “to bind back”. Both of these terms point more to a discipline of practice than any particular doctrine or dogma. Understood through the common metaphor of “path,” the only faith needed is a confidence that one can tread the path and a willingness to test the hypothesis that it leads to liberation. Gombrich also talks about the kind of religion that he calls “communal” which is characterized as a patter of action, solemnizing major milestones in a person’s life such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death, along with celebratory rituals, benedictions and the like. This communal religion is more social and centered around the ordering of society. With this understanding, he argues that Hinduism is at base a communal religion, conceptualized and codified in Brahmanical law books. An example of this is how marriage occupies the most important position among the sixteen sacred rites of India, after which, one is seen as entering into the householder stage of life. The Buddha, on the other hand, couldn’t care less about marriage, and in fact saw it and all other aspects of communal religion as something to be left behind as having nothing to do with liberation; in fact, they were often seen as obstacles to liberation! For this reason, for most of its history, Buddhism had no such rite as a “Buddhist wedding,” though various Buddhist cultures over time accommodated the cultural desire for it. So, back to our original question: Is Zen Naturalism a religion? The short answer is, yes, if we understand it as having liberation as its purpose. What distinguishes it from traditional Buddhism, however, is that liberation is not conceptualized as the end of the round of births and the escape from samsara, but the liberation from our conditioned patterns of reactivity and false identifications that lead to so much suffering. Zen Naturalism’s liberation project is not the world-wary attempt to leave the world altogether that is found in early and traditional Buddhism. And, at the same time, as a contemporary this-world oriented religion, is has deep respect for the communal religion’s aspects that celebrate life in community and society. Zen Naturalism calls for an active engagement to better life and the world for all beings. Rituals of celebration are designed to foster meaningful relations among the various beings in the world. Zen Naturalism does not seek meaning and validity in any transcendent realm of existence. Grounded in a scientific, naturalist understanding of the cosmos, we are fully at home, each of us a child of the cosmos, star babies and our religion is the remembrance of this reality. Click here for more information about Richard Gombrich

0 Comments

There is so much misunderstanding about what meditation is and because of this, I have sadly heard from many people that they "cannot meditate" when in actuality, we all meditate spontaneously sometimes multiple times a day.

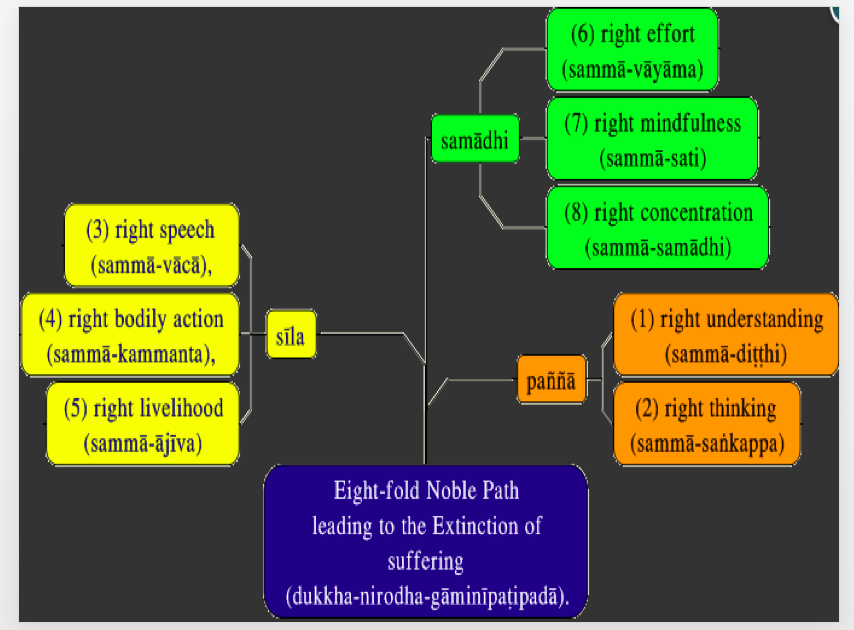

In this episode, I define terms and explain how concentration and mindfulness are two elements of all forms of meditation and that what you emphasize will determine the course of your meditation. In this episode, I also present the first of many practices I will be sharing on the podcast. I hope you enjoy it and find it helpful! For further reading about this, try this page of the Mindfulness Yoga Blog.  The Noble Eightfold Path of the Buddha is an 8-limbed model of yoga practice. In this episode, Pobsa situates the Buddha's yoga path in the context of other models from 4 to 15 limbs (anga). An example of the Buddha's pedagogical creativity is that he offers these eight limbs in two different formulations: as the Noble Eightfold Path, but also as the Threefold Training and the difference in the ordering of the limbs itself is a teaching!

The Eightfold Path begins with the two limbs associated with wisdom (prajna) to signify that there is wisdom behind one's decision to enter upon the path. Then there limbs of ethical training (sila) follows, showing that the heart, so to speak, of the path is the ethical commitment to non-harming (ahimsa) which itself prepares the mind for the deeper practices of meditation (samadhi) which make up the final three limbs of the path. Howegver, as the Threefold Training, we begin with sila as ethical training is the foundation of practice as well as permeating the other trainings. Sila sets us up for meditative training (samadhi) in order to access and cultivate greater, liberating wisdom (prajna). The image below shows the Threefold Training read left to right and the Eightfold Path read from the bottom to the top of the image. Note: This image uses the Pali terminology so the Sanskrit for wisdom prajna here is panna.  In this second episode of Pobsa's Dharma Lounge, the beautiful practice of dana is explored. As a form of "gift exchange," the practice of dana may be one of the most anti-capitalist forms of exchange based upon joy and not commodification. For many raised in the consumerist cultures of the west, to break out of a "fee for service" mentality can prove quite challenging and yet also amazingly liberating. The podcast is an example of dana as I do not take any advertising or sponsorship and there is no exclusive content only for "patrons" or "members." If you wish to share your support of this project, whether as a one-time offering or as a periodic sharing, you can be assured that all dana will be received gratefully!  In this first episode, I present an introduction of myself and my background, as well as an overview of what to expect from this podcast: mostly short episodes looking at a particular Buddhist teaching or practice; occasional conversations with other teachers and practitioners; and very occasional "salons" where a group of teachers and/or practitioners will discuss some theme related to Dharma.

I also argue that there is no one alive that is offering "original" Buddhism as all forms of Buddhism currently practiced are various interpretations of texts written down hundreds of years after the Buddha's death and even at the time of his death, there were already a variety of interpretations being offered. When I first came to Buddhist practice, a metaphor of a "Tree of Buddhism" was offered, with one root in "original Buddhism" and then a trunk with diverging branches. But now, we know that there is no single root and that a more accurate metaphor is of braided streams. For more about this, you may wish to read the first essay, "Whose Buddhism is Truest" in this free pdf from Linda Heuman: Shifting the Ground We Stand On |

This is where you'll find additional material and resources related to Podcast episodes and where you can comment, ask questions, share thoughts and experiences, or suggest topics for future episodes! ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed