|

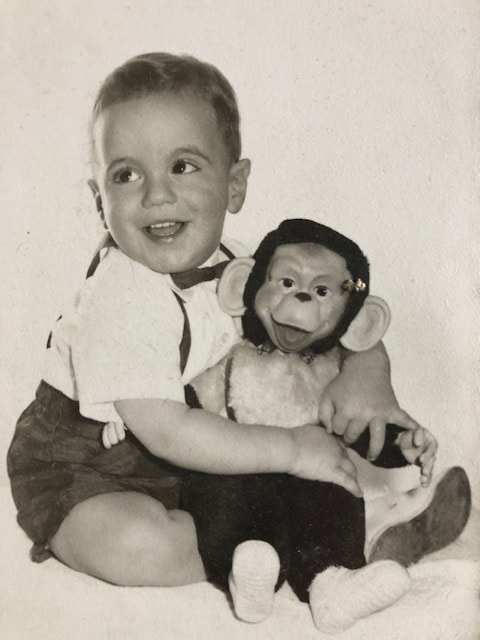

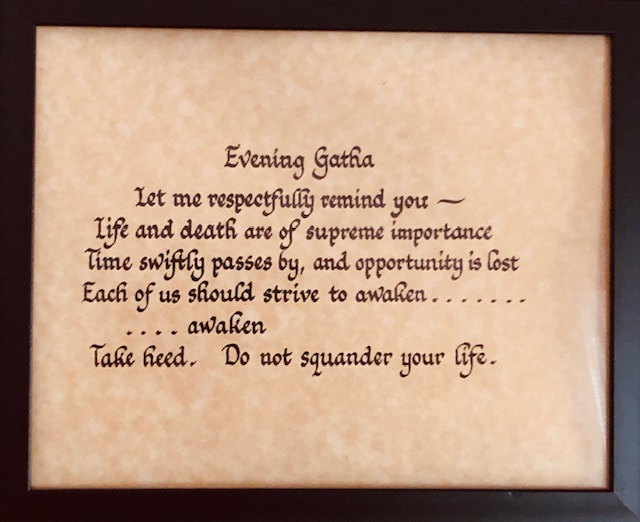

The earliest loss I can remember is when the girl next door left my prized monkey out in the rain. (Yes, that's me and my monkey in the photo). That monkey had been a gift from my father that he brought back for me from his trip to Cuba. Obviously, this was long before the US placed a prohibition on travel to Cuba. In fact, from photographic evidence, this had to be before the revolution ended in January 1959 with the overthrow of Fulgenico Batista, the US backed dictator. Thus, this loss occurred over 60 years ago, showing both the pervasiveness of loss and separation and the depth of feeling we may experience because after all these years I can still recall how hard I cried; how inconsolable I was when we saw the saturated monkey that my folks said had to now be thrown out. Since then there have been untold separations… from possessions, places, and people. My first two-wheeler, an Italian Racer brought from Italy by my grandmother destroyed in a terrible bike accident as well as the replacement with the banana seat and butterfly handlebars, stolen from my back yard. I moved out from the family home and have lived in many apartments and houses from Queens, to Manhattan to Brooklyn and then the Hudson Valley before moving to Eugene, Oregon and then to Tucson, Arizona. I’ve had many romantic relationships, including three marriages that have all ended in divorce. Of course, some separations and losses are easier than others. I don’t grieve the loss of any of the apartments I lived in, but there is still some sadness over leaving the Hudson Valley, the place I still think of as “home.” None of the divorces were easy to accept and move through, yet the last, four years later, still hurts, mainly because I became a father again during that marriage and though I’d been practicing Buddhism for decades, I had internalized the idea that we’d be together till my death (being older, the assumption was I’d be the one to die first). Also, I had imagined living together full-time with my daughter and now she lives with me half the time and half the time with her mom. After several days together, it still a bit of a pang to say goodbye when I drop her off at her mom's. So not all separations are one-time things; there are these little separations we all have in various ways throughout our lives. Everything changes because everything is impermanent. In fact, it’s a bit of a misnomer to call things “things” as if they were anything other than ever-changing dynamic processes. There is no solidity to experience at all. And it’s important to acknowledge that impermanence itself is not intrinsically painful: no one mourns the changes we desire. When we’re ill, we look to the change that healing brings. When lonely, we wish for change to bring love, camaraderie and comfort. It is all those changes that we do not anticipate or desire that bring a sense of loss, pain and grief that we shun or try to avoid. The way of the Buddha, however, is to not attempt to deny the impermanent nature of phenomena, nor cover up, deny or avoid our grief and sadness through the myriad ways we have found to attempt to do so from alcohol and drugs, to social media, as well as through spiritual bypassing, taking the teachings on equanimity and inauthentically assuming the posture of being ‘beyond the pain of loss' or disassociate and numb ourselves in the guise of being 'non-attached.' The noble teachings and practice of the Buddha is instead to lean into the pain in order to understand it with what the Buddha called “clear comprehension” in order to learn how to more skillfully navigate our losses and the pain they bring. Parents often experience impermanence ambivalently. I remember when my younger daughter was just born, she made these sweet little grunting sighs while she slept and while she nursed and I was very conscious that these sounds would only be made for a short time; that eventually they would stop and other sounds – and words – would be made. There is a sadness over the loss of those sounds and I’m delighted to hear her voice now as she explains what she’s been doing at school. I loved the days of wearing her pressed against my chest as we walked to the café where I’d relax over a cappuccino while she napped, her head nestled on my shoulder and now I am delighted to walk with her to the café where we discuss her latest projects over the bagel and hot chocolate she orders for herself. And up to second grade, she would enact a ritual each morning when I dropped her off at school: very strong hug and kiss followed by a moderate hug and kiss and ending with an air hug and air kiss. Nowadays, I’m glad that she still gives me a short, rather perfunctory hug and immediately turns to join her friends in play before class. No parent would have it any other way, and yet there’s that little tug at the heart in response to the change. Perhaps a kind of change or separation that is most subtle and difficult to acknowledge or accept is when our very self-identity shifts. As we age, we are separated from our young selves and there is almost always something bittersweet about that. That’s why nostalgia feels good and bad. We may think of ourselves as being a certain way, feeling certain feelings and thinking specific ways and then life throws a curve ball and we barely recognize ourselves. I was teaching a series of workshops in Kentucky, and had begun to write another book when I received the phone call from my urologist that changed the direction of my life. No longer am I that guy with the strong constitution who is never sick. I became 'a cancer patient.' I have found that opening to change, as difficult as it can often be, ultimately leads to more peace of mind than living in denial of the reality of change and separation. And even during that perfunctory hug, I reflect on how there is, really, no guarantee that I will see my daughter again so I don't want to take any moment of connection for granted. I’ve survived an incredibly serous car accident that could easily have caused my death. And that sudden loss remains a possibility. And that’s what this remembrance is for: to wake us up to the reality of uncertainty. To remind us that all is constantly changing in order that we should not take what we love now for granted. If we fail to keep this in mind, then we lose what we have even while we have it. Cancer treatment is expensive in the US, even with insurance. If you are moved to support me through this time, any dana you can share is greatly appreciated.

2 Comments

The Hudson Valley is my home of over 40 years. I couldn't agree more that it would be difficult to leave. There's so much beauty and community. I love even just going to my local garden center and talking with people who are always friendly and knowledgable.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorPoepsa Frank Jude Boccio is a yoga teacher and zen buddhist dharma teacher living in Tucson, AZ. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed